If anyone is looking for the definitive definition (if you will) of biotechnology, an inquiry to Professor Google quickly reveals the following:

“Biotechnology is the use of biology to solve problems and make useful products. The most prominent area of biotechnology is the production of therapeutic proteins and other drugs through genetic engineering.” That’s according to Brittanica.

Next up, Professor Google also offered Merriam-Webster’s take, calling it, “The manipulation (as through genetic engineering) of living organisms or their components to produce useful, usually commercial products (such as pest resistant crops, new bacterial strains or novel pharmaceuticals).” It also noted “any of various applications of biological science used in such manipulation.”

The point is, especially as a relatively new and separate sector, biotechnology can be interpreted different ways from different perspectives.

“Life sciences is a broad term,” said Matt Szuhaj, vice president with the Oakland, Calif.-based Strategic Development Group. “It combines the chemistry and/or small molecules of the pharmaceutical industry with biology, and you’re dealing with natural processes of the body. They’re different sciences.”

But that’s what makes biotech so fascinating, too. “That makes tuning in to the various sectors of the industry important,” said Szuhaj, “because we all know that it’s going to grow.” And grow is just what it’s projected to do: the U.S. biotechnology market was valued at $621.55 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $1,794.11 billion by 2033, registering a compound annual growth rate of 12.5 percent from 2024 to 2033, according to BioSpace.

But today, just how much that current number will rise and how soon is the question, with the new administration in place and having announced spending cuts that are already affecting the market.

Multi-Benefits

Szuhaj discussed an instance where further investment would be beneficial today. That would be in GLP (more commonly known as Ozempic, as in the TV commercials), which “is marketed to diabetics as a way to lose weight. It affects the processes of the brain related to that motive,” said Szuhaj. “It can also be applied to any addictions, and thus can be spun off for alcohol addiction and other compulsions.

“So while it may not be approved reimbursable, these therapies can eventually have multiple benefits,” he said. “Big pharma is supporting that.”

Szuhaj underscored that comment when he stated that cell and gene therapy “is going to grow for blood-borne cancers, but they have other uses, too. They use T-cells, which are used to produce endorphins that can be used to treat additions to chemicals, like opioids, including fentanyl; it can also be used for pain management, for example, among a variety to other uses.”

He went on to cite the various RNA technologies for vaccines for cancers, eye disease and pandemic flu, and while, “That’s what people know,” he said, “there’s more to it. That area is going to grow.”

Slow Down?

With the biotech field primed for huge growth, Szuhaj has more to talk about, including regenerative medicine, “which is primarily developed and utilized by the military. It’s focused on regrowing muscle tissues with your own cells, so it won’t be rejected,” he said. “Researchers can already regrow an ear, are getting close to regrowing a kidney and are working on the vascular systems.”

“Today, [it’s] used for traumatic injuries,” said Szuhaj, “but we’ll see the uses expand beyond the military to the general public.”

But next comes his “However” moment.

“This may all slow down,” Szuhaj said, “due to the uncertainty around the National Institutes for Health and National Science Foundation funding.”

That’s made parties from many corners of the industry nervous. For instance, he pointed out a new antibody drug that conjugates to identify a cancer cell and destroys it. “Such precision medicine is especially important,” he said, “for people who are genetically predisposed to certain diseases or a vitamin or nutrition problem.”

“With the additional advancements in computing,” said Szuhaj, “you can now tailor certain therapies to the individual patient.”

Offering the example of medical device monitoring for diabetes type 1 and 2, he also cited the coming rise in home treatment of chronic diseases. “Take kidney failure, or hemodialysis, for instance,” he said. “In the future, the ‘hospital’ beds will be all over the community, with diagnostics via Zoom or a simple phone call to the nurse’s station.”

“No one has scaled that model yet, but we’re evolving toward that,” said Szuhaj. “The industry is also building clinics to get EKGs and MRIs into more rural areas.”

Robust Sector

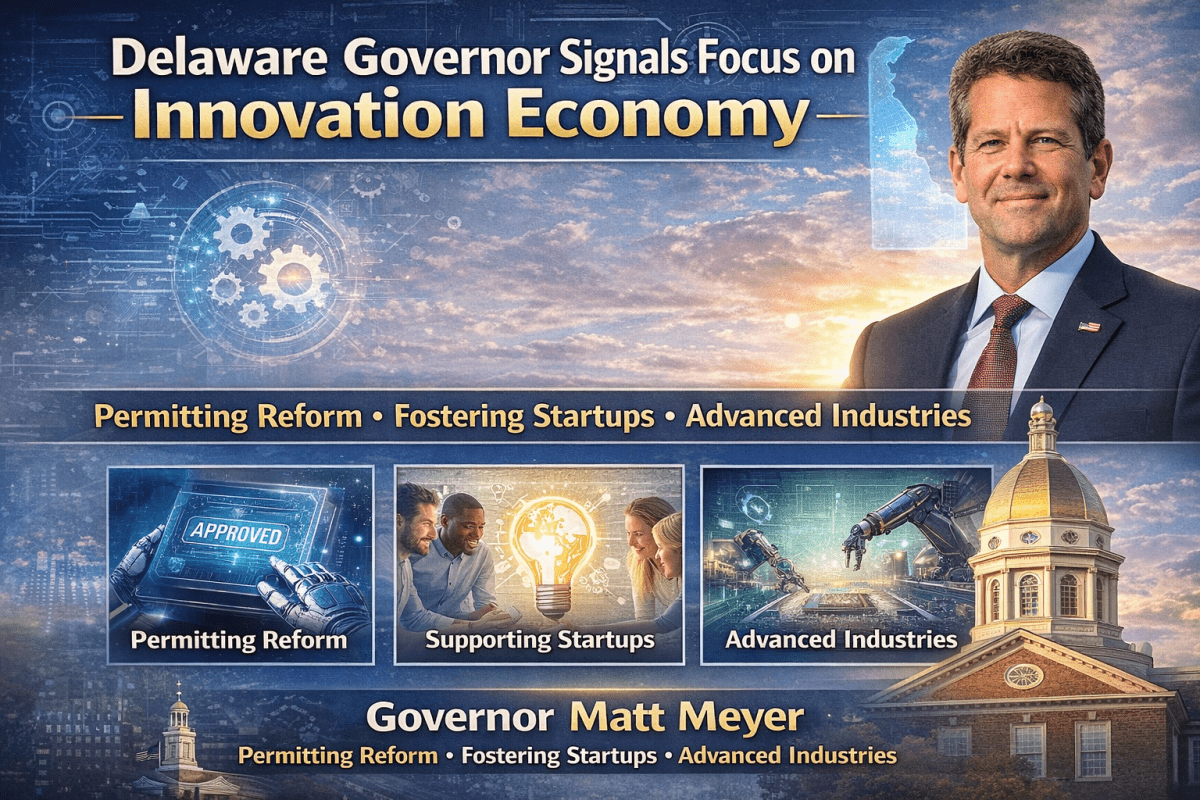

But despite the recent worries based on government cuts, “What I see today is a robust startup sector and strong support for it in the biotech industry,” said Alisa Morss Clyne, ADVANCE professor in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland College Park.

“I was recently at the Maryland MedTech Summit on our campus,” said Morss Clyne, “and was happy to discover many exciting ideas in sectors, including women’s health, orthopaedics and cardiovascular health.”

“The American Heart Association even had its venture capital group at the event,” she said. “Many of these startups are coming out of academia and from doctors who are finding various needs via their medical practices.”

One that note, she also discussed the changing relationship between academia and industry. “For many years, the federal government has funded research from universities,” said Morss Clyne. “Today, it looks like much of that funding will decrease or disappear, and we’re uncertain how the biotech industry will shift. So will more funding come more from the corporations?”

“We’re hoping it will,” she said, echoing Szuhaj, “because if not, there will be less innovation. And that’s a problem.”

VC Sidelined

While the term ‘biohealth’ “didn’t exist 15 years ago,” said Richard Bendis, CEO of Rockville, Md.-based BioHealth Innovation, who defines it as “a product of the convergence between therapeutics, medical devices and vaccines with technology, artificial intelligence, digital health, machine learning and quantum computing. So we created that term.”

What that’s led to is today’s robust market in life sciences, pharma, etc. That was the case until COVID-19 hit, anyway.

At that point, “everything became all things vaccines and how we can treat people who had that disease. When the federal government spent billions of dollars to chase the pandemic, the companies shifted their efforts toward those dollars and it was a money chase,” said Bendis. “So there was a slowdown in the traditional life sciences market.”

“So we got off track a bit from where we had been, (which encompassed) robust growth in venture capital, medical devices and biotech.” That “affected our target market,” he said. “However, post COVID-19 there has been a nice recovery in that area, as companies have returned to taking the long-term approach.”

Then came this latest twist in the road. As the U.S. reached the end of President Biden’s term and is now into the early months of the Trump administration, “we’re experiencing another correction,” said Bendis.

“Now, much of the industry and all of the people who were investing in research and development have gone to later-stage assets, like Stage 1 and 2 clinical trials, that are farther ahead,” he said, “but those that are pre-clinical are facing challenges in the early stage. That has also been hard for companies getting high-risk venture capital and getting traction. Now the $47 billion in research that had been coming from NIH has changed dramatically in the last three months.”

But even in the face of such uncertainty in the market, Bendis could point to “a few bright spots,” such as CAR T and cell therapy. “Researchers are seeing significant improvements in treatments for patients with these therapies,” he said, “some of which are in platform technologies for deliveries to many areas of the body that are difficult to reach.”

Still, in the venture capital market, “lots of money is sitting on the sidelines,” he said, “because venture capital and private equity firms have raised the money, but there are not as many exit strategies as there have been in past.”

“So, if you’re a bio investor and need returns,” said Bendis, “it may take seven to ten years as investors are trying to reduce their risk in the research pipeline by investing in technologies that have moved closer to market.” However, “This is having a huge negative impact on the early stage investment markets across the country.”

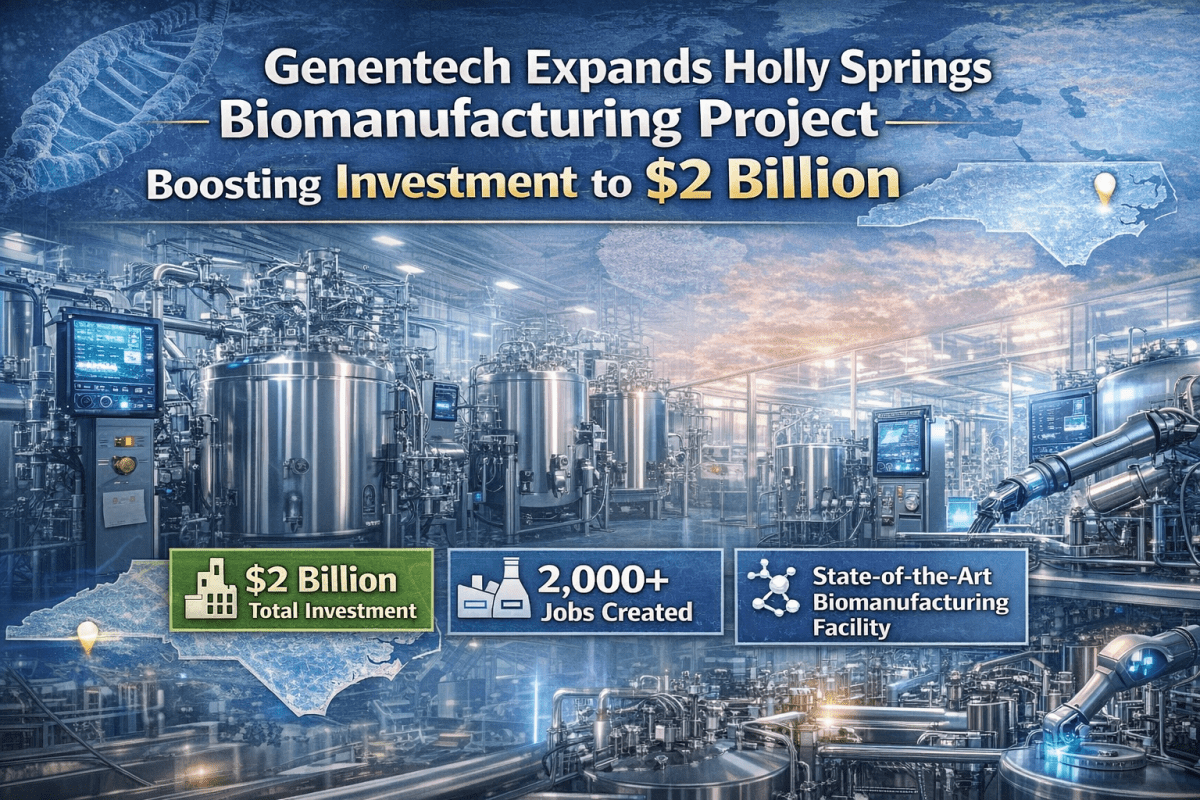

While this is a national issue, the areas that will be hit hardest are the traditional biotech clusters like the Baltimore-Washington Corridor, San Francisco, North Carolina’s Research Triangle, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. “The potential short-term returns on investment,” he said, “are not as available as they were during our recent upcycle.”

The effect of today’s market turbulence also affects commercial real estate development. “In recent times, companies built expensive wet lab spec space that is suddenly not as desirable,” said Bendis.

“That’s tough, but in a boom market vacancy can drop to three to five percent,” he said. “However, the double-whammy of the pandemic and post-COVID-19, with the new administration’s life science federal budget cuts, are creating a second challenge for property owners and managers.”

Talent Influx

“I think one of the biggest challenges in the overall industry right now is uncertainty, and investors don’t like that in any industry. So they are waiting to see what’s going to happen,” said Julie Lenzer, chief innovation officer for Manchester, N.H.-based Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute (ARMI), which is removing the manufacturing, regulatory and commercialization barriers for biomanufactured cell-based therapies, such as breakthroughs to treat type 1 diabetes.

That progress has spurred her positive outlook. “We’ve been seeing regulatory breakthroughs with promising therapies for treating various health issues and diseases,” said Lenzer, noting that ARMI received additional funding in 2024 from the Department of Defense and the Department of Commerce.

She was able to offer an optimistic note on what’s to come. “There’s no indication,” she said, “that our funding situation is changing.”

Lenzer offered more good news for an industry that is perpetually seeking qualified workers―it’s receiving an unexpected influx of talent. “They’re former employees of the federal government who lost their jobs,” she said, “or are simply transitioning for various reasons.”

While adding that “AI in biotech is as hot as it is everywhere,” she also expressed optimism about getting ARMI helping their members get their therapies to patients much sooner than expected, despite today’s challenges.

“Right now, we’re focused on executing,” she said of ARMI’s efforts. “Several member products have been showing great promise, including one with a path to cure Type 1 Diabetes in the next two to five years.”

The standard concerns about the new economic mix were also expressed by Doug Edgeton, president and CEO of Durham, N.C.-based NCBiotech, who also underscored AI’s growing presence and where it could lead.

“Major trends in biotech,” said Edgeton, “include how AI will assist in drug discovery and development, further advancement of the bioeconomy, how cell and gene therapy will advance (and how gene editing will progress), and how biotech startups will fare as the investment community reacts to the current economic climate.”

While the industry is waiting “to see how activities in the federal government and in the investment community will shake out,” he said, “there’s also considerable uncertainty about NIH funding of research, staffing changes at the Food & Drug Administration and how tariffs will affect the industry.”

But on “the other side of that coin,” said Edgeton, “is the potential for onshoring of large biomanufacturing operations to meet U.S. demand.”

Built to Thrive

Edgeton was also careful to stress the main strength of the biotech industry.

“It’s built on innovation. The scientists and entrepreneurs in biotech are resourceful and inventive, and find unique ways to develop innovative solutions for the world’s most difficult problems,” he said. “Despite uncertain times, these innovators have delivered and will continue to deliver.”

So despite its issues, there is still great progress being made in biotech, especially considering that its basic reason for being remains delivering better treatment to the masses and improving health care for all.

Reaching that goal can be “as simple as the use of wearables, like an Apple Watch. We’re in the middle of an adoption trend,” Szujah said. “It’s about integration into the health care system.”

Always looming here is the fact that “no one has a crystal ball,” said Bendis. “So where do you place your bets across the various biotech sectors? Everyone is enamored with AI, but how many products can you point to? AI is more of an enabling technology than a product category, similar to nanotechnology.”

“Today, we’re going through a new biohealth investment cycle,” Bendis said. “Only time will tell the winners and losers.”